Aquaculture in the Philippines: The Top 10 Diseases Shrimp Farmers Should Be Aware Of

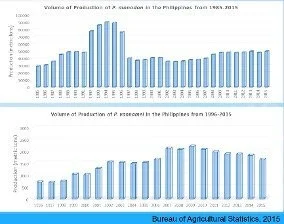

Shrimp are one of the most popular aquaculture species in the Philippines. Shrimp farming can be highly profitable, with higher harvest rates and relatively low production costs compared to other species when standardized, sustainable aquaculture approaches are followed.

Disease outbreaks over the last two decades, however, have led to dramatic declines in the shrimp output and challenges for the Philippines claiming its place as a global shrimp leader.

These diseases can be bacterial, protozoan, or viral. Their growth is often enabled by poor nutritional or environmental factors which provide food for the pathogens or apply immune stress to the shrimp.

To help the local shrimp farming community, we’ve compiled a list of the Top 10 Disease Threats facing Filipino shrimp farming today:

White Feces Disease (WFD)

White Spot Disease (WSD)

Heptopancreatic microsporidiosis (HPM)

Early Mortality Syndrome (EMS)

Luminous Vibriosis

Shell Disease

Filamentous Bacterial Disease

Ciliate Infestation

Chronic Soft-Shell Syndrome

Black Gill Disease

The Major Diseases in Philippine Shrimp Production

Figure 1. White Spot Syndrome in Shrimp. (Hossain et al, 2014. Prevalence and distribution of White Spot Syndrome Virus in cultured shrimp.)

White Feces Disease

WFD is a challenging mystery for the aquaculture disease, as its exact cause is unknown. A common symptom of White Feces Disease (WFD) in shrimp is the change in color of the gut. Compared to a normal shrimp, the gut is pale white instead of a darkish brown color. The feces excreted by the shrimp is also more buoyant than normal as the white excrement floats to the surface of the pond. The exoskeleton of infected shrimp become loose, and there is a dark discoloration on the gills.

Studies show that shrimp with WFD lose appetite and can even reach up to 60% mortality. White Feces Disease is associated with many environmental factors such as poor water quality, pond bottom sludge accumulation, and plankton blooms. Some growing practices such as high stocking densities and bad feed management have also been connected to the disease.

Since the exact cause of WFD is still unknown, it is best to follow biosecurity and water management best practices to reduce the risk of its occurrence.

White Spot Disease

In 2014, an outbreak of the White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) in the Philippines reduced local shrimp production from 1-1.5 ton per hectare to 200 kilos or less. The virus causes White Spot Disease (WSD) with symptoms including white spots on the exoskeleton, with sizes ranging from barely visible to 3 mm in diameter.

However, the white spots are actually not a reliable sign to diagnose the disease because these can also be caused by environmental factors such as high pH of the water or even by some other bacteria. Shrimp affected by WSD exhibit a loss in appetite and abnormal swimming

Figure 1. White Spot Syndrome in Shrimp. (Hossain et al, 2014. Prevalence and distribution of White Spot Syndrome Virus in cultured shrimp.)

patterns such as swimming on their side, gathering around the edges of the pond, or swimming near the surface.

It is important that farmers check if the stock contains WSSV and to destroy the stock as soon as it is proven to be infected. The water quality must be kept in check, regularly cleaned, and monitored for possible infective sources.

Hepatopancreatic Microsporidiosis

The spore-forming microsporidian called Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP) is the main cause of Heptopancreatic microsporidiosis (HPM). The disease is slowly spreading across shrimp farms in Asian countries, such as the Philippines, creating large numbers of loss in the industry. Shrimp are infected by the EHP when they consume contaminated feed and feces from already infected shrimp. A common symptom of the disease is a milky white substance on the abdominal area of the shrimp. While HPM is not scientifically known to cause high death rates in shrimp, it is reported to produce smaller shrimp.

There is no known cure for HPM. An infected pond must be decontaminated thoroughly and chlorine must be added before it is restocked. Due to the extensive measures to be done for decontamination, prevention is the most cost-effective manner to reduce its effects. Farmers must regularly clean and disinfect the pond water and must monitor the presence of EHP in common feed for brood stock. Eggs should also be disinfected by using chlorinated water.

Early Mortality Syndrome

Also known as “acute hepatopan-creatic necrosis disease” (AHPND), the Early Mortality Syndrome (EMS) is caused by Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Penaeid shrimp. It affects the post larval stage and can be diagnosed roughly 20-30 days after stocking. According to reports, the disease can cause up to 100% mortality in Penaeid shrimp.

To prevent, farmers need to focus on the quality broodstock and postlarvae (PL). Farm management practices, such as cleaning the pond bottom and preparing the pond water, determining the stocking density, choosing feeds and feeding practices, and monitoring water quality fluctuations must be observed as these were found to be connected to AHPND outbreaks. De Schryver et al. (2014) found that while it is important to disinfect ponds, it is recommended to grow the shrimp in water that has a biodiverse microbial system. This can be done by adding probiotics to the pond water.

Luminous Vibriosis

One of the major disease problems in grow-out shrimp culture is the Luminous Vibriosis. This disease, caused by the bacteria Vibrio harveyi, V. splendidus and other luminescent vibrios, affects the eggs, larvae, post larvae and juveniles of the shrimp. Vibriosis weakens the larvae and juveniles. Larvae become opaque-white while the juveniles have discolored portions on the body.

As the common name of the disease suggests, the larvae glow green when in total darkness. Luminous Vibriosis can be deadly to the shrimp and has potential to kill up to 100% of the shrimp population. In 2008, the Philippines’ leading province for intensive shrimp culture, Negros Occidental, experienced an outbreak that left only 20% of the ponds operational.

To prevent this, it is best to monitor the shrimp during their early stages and to check the bacteria present via water sample tests regularly. It is also advisable to create microbial diversity in the water to competitively exclude the pathogens by using probiotics.

Shell Disease

Shell Disease, also known as Brown/Black Spot Disease, Black Rot, or even the Necrosis of Appendages is caused by shell-breaking bacteria within the Vibrio, Aeromonas and Pseudomonas families. This disease affects shrimp from their larval stage up to adulthood. During the larval and post-larval stages, the affected limb has an appearance like a cigarette butt – dark brown and ashy in color with obvious blisters. These blisters usually contain a substance with a gel like texture and can appear large enough to form a bulge on the shrimp’s body.

The disease can cause problems with molting and can erode a large portion of the blisters which cause the water to emit a foul odor. The affected shrimp can also become cannibalistic or die from stress.

It is important to maintain good water quality to prevent shell disease. The organic load of the water must be maintained at a low level by removing dead shrimp and molted exoskeletons which can contain or feed unwanted bacteria.

Filamentous Bacterial Disease

Filamentous Bacterial Disease is another disease that shrimp farmers should look out for. The disease is caused by Leucothrix sp. and can affect the shrimp from its larval stage to adulthood. If observed under a microscope, the body and the gills of the shrimp will appear to have thread-like growth that are all colorless.

When infected with the disease, the shrimp’s eggs have filaments on the surface which can cause problems with respiration or hatching. If the shrimp’s gills are affected, the bacteria block the respiratory surfaces and can also cause problems with respiration. Besides respiratory failure, the bacterial disease can cause the larvae and post larvae to have problems with normal movement and molting. There is also a possibility that the grown shrimps can die.

Good water quality must be observed and maintained – in particular, dissolved oxygen must be maintained at a level that greater than 5 ppm and the organic matter level must remain low.

Ciliate Infestation

A protozoan-caused disease, Ciliate Infestation can be caused by the protozoa Vorticella, Epistylis, Zoothamnium, Acineta, or Ephelota during any stage of the life of shrimp. Its common symptoms include a fuzzy texture on the shell and gills of juveniles and adults as well as having reddish to brownish gills. The shrimp also experience a lack of appetite and can have difficulty moving when the protozoa is present in large numbers. When the protozoa are present in the gills, respiratory problems can also occur, especially when the dissolved oxygen levels are low.

The best way to avoid this disease is to closely monitor the dissolved oxygen level. Farmers should also avoid high organic loads, heavy siltation, and turbidity in the water as these also affect the dissolved oxygen levels.

Microsporidiosis

Microsporidiosis is another protozoan disease. Also called White Ovaries or Microporidian Infection, this disease is caused by microsporadia - protozoans that can only be seen on the infected tissues under a microscope. Juvenile and adult shrimp often exhibit the disease when there are tissues or organs that turn an opaque white.

The parasite can replace the affected tissue and can cause sterility among shrimp, turning the ovaries white. While the infection rate is usually less than 10%, the parasitic Microsporadia has a high chance of causing microsporidiosis.

To prevent the growth of the protozoa, it is good practice to disinfect culture facilities with chlorine or iodine-containing compounds. Infected shrimp must be isolated and destroyed by burning or boiling. The most effective way to prevent possible spread of the disease is to identify the reservoir species and to discontinue the growth for commercial production.

Chronic Soft-Shell Syndrome

Disease in shrimp can also be caused by a lack of nutrients, as exhibited by Chronic Soft-shell syndrome. Also known as soft-shelling, the shrimp grow a thin and persistently soft shell for several weeks. The shell surface is often dark, rough and wrinkled, weakening the shrimp.

Unlike normal molting, the shells of the infected shrimp are not clean and smooth and take much longer than the normal 1-2 days to harden. Since the shrimp are too weak and prone to more damage because of the soft shell, they grow very slowly and eventually die. Weak shrimp are prone to be damaged or even eaten by shrimp in the same container.

To lessen the chances of Soft-Shell, the pond or container to be used must be flushed thoroughly after harvesting, especially if pesticide contamination is possible. Supplementary feed, such as mussel meat, may be given to the shrimp in order to augment these needed nutrients.

Black Gill Disease

Black Gill Disease can be caused by the deficiency of ascorbic acid in the diet of the shrimp, as well as possible contaminants in the water - such as cadmium, copper, oil, ammonia and nitrate. High organic load caused by residual feed or debris in the containment area can also cause this, as it leads to high levels of nitrogen in forms that are toxic to the shrimp.

The disease causes physical signs such as discoloration or a substance to form on the back side of the shrimps. It can also cause a loss of appetite, difficulty with respiration, secondary infection by pests and can lead to death.

To avoid this, the shrimp must never be overfed. As with other methods, keep the containment area clean and conducive for growing the shrimp.

Disease Management in Aquaculture

Treatments for these diseases are limited and costly. While certain antibiotics can be used, the best way to fight disease is to prevent it.

This is best done by ensuring that the water quality is optimal for shrimp growth. Here are three key elements of good water treatment.

Track and promote dissolved oxygen levels. Based on microorganism activity, this may require the addition of artificial aeration. Take regular readings, record these readings in a journal or spreadsheet, and act proactively to remediate levels if they begin to decline.

Actively eliminate waste build-up. Waste accumulation is significant in pond-style shrimp farming, coming from excess feed, shrimp feces, and dead shrimp carcasses. All of these decaying organic materials can be food sources for the types of pathogenic bacteria or protozoa that cause these diseases. Ammonia is a great mid-season indicator of organic waste levels. Track ammonia levels at least weekly (ideally daily) and act aggressively if numbers rise.

Implement and monitor strict biosecurity standards. Physically eliminate contamination through stringent checks on people, water, and equipment shared across ponds. By following these standards contaminants can be excluded, and if they do enter, can be kept contained to small areas.

Probiotics: A tool for proactive disease management

Probiotics, or beneficial bacteria, are a powerful tool to support farmers preventative disease treatments. Through their decomposition of nitrogen and phosphorus, they reduce blue-green algae and other major oxygen competitors – ensuring healthy dissolved oxygen levels. Many species, particularly of the bacillus family, decompose organic waste, serving as a clean-up tool for waste accumulation on pond bottoms. Further, they outcompete many harmful bacteria – such as those mentioned here – for nutrients, greatly reducing their ability to survive and infect the shrimp.

Connect with our team to learn about how our aquaculture probiotics can proactively treat your water, enhance your shrimp immune system, and help you prevent these diseases.

References

AftabUddin, S., Roman, W. U., Hasan, C. K., Ahmed, M., Rahman, H., & Siddique, M. A. M. (2017). First incidence of loose-shell syndrome disease in the giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon from the brackish water ponds in Bangladesh. Journal of Applied Animal Research, 46(1), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2017.1285771

Albarico, F. P. J. B., & Pador, E. L. (2019). Chemical and Microbial Analyses of Organic Milkfish Farm in Negros Occidental, Philippines. Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 7(2), 41–46. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334112718_Chemical_and_Microbial_Analyses_of_Organic_Milkfish_Farm_in_Negros_Occidental_Philippines

Cruz, M. (2014, April 21). Lawmaker warns of virus that affects crustaceans. Manila Standard. https://manilastandardtoday.com/news/-provinces/145523/lawmaker-warns-of-virus-that-affects-crustaceans.html

de la Peña, L., Cabillon, N., Catedral, D., Amar, E., Usero, R., Monotilla, W., Calpe, A., Fernandez, D., & Saloma, C. (2015). Acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) outbreaks in Penaeus vannamei and P. monodon cultured in the Philippines. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 116(3), 251–254. Inter-Research Science Publisher. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao02919

De Schryver, P., Defoirdt, T., & Sorgeloos, P. (2014). Early Mortality Syndrome Outbreaks: A Microbial Management Issue in Shrimp Farming? PLoS Pathogens, 10(4), e1003919. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003919

Farzanfar, A. (2006). The use of probiotics in shrimp aquaculture: Table 1. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, 48(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695x.2006.00116.x

Guerrero, R. D. (2008). Eco-Friendly Fish Farm Management and Production of Safe Aquaculture Foods in the Philippines. Semantic Scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Eco-Friendly-Fish-Farm-Management-and-Production-of-Guerrero/1cb357d76f53072a0e306d0e6a2d2cba2b6a4617

Guerrero, R. D., & Fernandez, P. R. (2018). Aquaculture and Water Quality Management in the Philippines. Global Issues in Water Policy, 8, 143–162. Springer Link. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70969-7_7

Lavilla-Pitogo, C. R., Lio-Po, G. D., Cruz-Lacierda, E. R., Alapide-Tendencia, E. V., & de la Peña, L. D. (2000, July). Diseases of Penaeid Shrimps in the Philippines (Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines (ed.)). Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center/Aquaculture Department. https://www.seafdec.org.ph/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/aem16.pdf

Leaño, E. M., Lavilla-Pitogo, C. R., & Paner, M. G. (1998). Bacterial flora in the hepatopancreas of pond-reared Penaeus monodon juveniles with luminous vibriosis. Aquaculture, 164(1–4), 367–374. Science Direct. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0044-8486(98)00201-4

Lima, J. S. G., Rivera, E. C., & Focken, U. (2012). Emergy evaluation of organic and conventional marine shrimp farms in Guaraíra Lagoon, Brazil. Journal of Cleaner Production, 35, 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.05.009

Mastan, S. A. (2015). INCIDENCES OF WHITE FECES SYNDROME (WFS) IN FARM-REARED SHRIMP, LITOPENAEUS VANNAMEI, ANDHRA PRADESH. Www.Academia.Edu, 5(9). https://www.academia.edu/16561050/INCIDENCES_OF_WHITE_FECES_SYNDROME_WFS_IN_FARM-REARED_SHRIMP_LITOPENAEUS_VANNAMEI_ANDHRA_PRADESH

Network of Aquculture Centres In Asia-Pacific. (2017, March 1). Report of the fifteenth meeting of the Asia Regional Advisory Group on Aquatic Animal Health, 21-23 November 2016. Network of Aquaculture Centres in Asia-Pacific. https://enaca.org/?id=619

OIE (World Organization for Animal Health). (2015). Whitespot disease. Manual of Diagnostic Tests for Aquatic Animals. https://www.oie.int/index.php?id=2439&L=0&htmfile=chapitre_wsd.htm

Poh, Y. T. (2016). White Feces Disease in shrimp. Www.Academia.Edu, 12(1). https://www.academia.edu/24697572/White_Feces_Disease_in_shrimp

Putth, S., & Polchana, J. (2016). Current status and impact of early mortality syndrome (EMS)/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) and hepatopancreatic microsporidiosis (HPM) outbreaks on Thailand s shrimp farming. Repository.Seafdec.Org.Ph; Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center. http://hdl.handle.net/10862/3094

ROMANA-EGUIA, M. R. R., LAGMAN, M. C. A., BASIAO, Z. U., & IKEDA, M. (2019). Genetic Research Initiatives for Sustainable Aquaculture Production in the Philippines. Journal of Integrated Field Science, 16(24), 4–7. Field Science Center, Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tohoku University. http://hdl.handle.net/10097/00125666

Salachan, P. V., Jaroenlak, P., Thitamadee, S., Itsathitphaisarn, O., & Sritunyalucksana, K. (2017). Laboratory cohabitation challenge model for shrimp hepatopancreatic microsporidiosis (HPM) caused by Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP). BMC Veterinary Research, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-016-0923-1

Singh, A. S., Devi, M. S., & Singh, A. A. (2011). Organic aquaculture: Sustainable and superior production The Concept of Organic Aquaculture. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 63–66. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230642011_Organic_aquaculture_Sustainable_and_superior_production_The_Concept_of_Organic_Aquaculture/citation/download

Somboon, M., Purivirojkul, W., Limsuwan, C., & Chuchird, N. (2012). Effect of Vibrio spp. in White Feces Infected Shrimp in Chanthaburi, Thailand. Journal of Fisheries and Environment, 36(1), 7–15. https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JFE/article/view/80769

Tangprasittipap, A., Srisala, J., Chouwdee, S., Somboon, M., Chuchird, N., Limsuwan, C., Srisuvan, T., Flegel, T. W., & Sritunyalucksana, K. (2013). The microsporidian Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei is not the cause of white feces syndrome in whiteleg shrimp Penaeus (Litopenaeus) vannamei. BMC Veterinary Research, 9(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-9-139

Vergel, J. C. V. (2017). Current Trends in the Philippines’ Shrimp Aquaculture lndustry:A Booming Blue Economy in the Pacific. Oceanography & Fisheries Open Access Journal, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.19080/ofoaj.2017.05.555668

Wang, Z., Shi, C., Wang, H., Wan, X., Zhang, Q., Song, X., Li, G., Gong, M., Ye, S., Xie, G., & Huang, J. (2020). A novel research on isolation and characterization of Photobacterium damselae subsp . damselae from Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei , displaying black gill disease cultured in China. Journal of Fish Diseases, 43(5), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfd.13153